Culture

Chahta Culture Art Forms

Taposhshik Imma (Basketry)

Like many facets of Choctaw life, basketry is steeped in Tribal culture. Part of Choctaw life for centuries, it is a practice that blends tradition with innovation. In years gone by, baskets were used in the field and in the home. Modern times see the baskets holding a place in treasured Choctaw collections.

Basketry is an art form that starts with the harvesting of the swamp cane – native to Mississippi creek banks. It has become increasingly difficult to find swamp cane in its original wild setting. However, Tribal programs have and continue to establish swamp cane fields for artisans. It is important to the Choctaw that swamp cane is readily available so the art of Choctaw basketry is preserved.

The method of cutting and preparing the cane is the same used by Choctaw for generations. Fall is the ideal time to gather the cane, although it is hardly an easy task, given that wet, swampy areas are its natural habitat. Length of the cane vary, although most basket makers like to work with cane that measures at least six feet long.

Once the cane is cut, the weaver uses a small, sharp knife to slice the thin top layer into strips. A skilled maker can get four to six strips from one piece of cane, but that is a matter of individual preference.

Dyeing the strips is the next step. For many years, basket makers used natural materials such as berries, flowers, roots or bark to color the cane. Modern times have seen the introduction of commercial dyes due to their durability and wide range of colors available. Basket makers create a variety of patterns by weaving together the colored and natural strips of cane. While traditional forms such as the egg basket and traditional patterns like the diamond design are common, many basket makers like to experiment with color, pattern and shape.

The Choctaw have kept with the times, but still hold strong to their traditions. The makers express themselves the same way other artists do – with technique, imagination, and aesthetics.

Ilífokka (Clothing)

The colorful Choctaw dresses worn by Tribal women are handmade and likely find their inspiration from a 19th century design. No pattern exists for the dresses, which include a bodice with a fitted waist and a long, full skirt trimmed with ruffles and hand-sewn appliqué. A white apron, trimmed in the color of the dress, completes the woman’s traditional outfit.

Shirts for men feature either a round neckline or an open collar and appliqué work on the front and sleeves.

Choctaw dresses usually are trimmed with one of three motifs: full diamond, half diamond, or series of circles and crosses. The last motif may represent stickball and stickball sticks, but it may also have origins in earlier designs. The diamond design, which is often seen on Choctaw baskets as well, is said to represent the eastern diamondback rattlesnake.

Today, most Choctaw wear Choctaw dresses and shirts mainly for special occasions. They are made from cotton fabric and in solid colors with a contrasting trim. Occasionally, women choose silk or velvet fabric for traditional dresses – usually for events such as the Choctaw Indian Princess Pageant.

There are a few elders who still prefer to wear Choctaw dresses for their everyday clothing. Those are made from print fabric and are shorter than dresses worn for dancing. Instead of time-consuming hand appliqué, the traditional dresses are sometimes trimmed with commercial fabric. The apron may be worn with these dresses as well.

Shikalla Átoba (Beadwork)

Beadwork is a feature often worn with traditional Choctaw clothing for both men and women. A common set for women consists of a belt, medallion, collar necklaces, earrings, ribbon lapel pins and a handkerchief lapel pin. Designs and colors are the artist’s preference, and many women also wear round combs in their hair with their Choctaw dresses. Historical drawings and photographs suggest that originally these combs were made from silver or other metal.

Twentieth century photographs show Choctaw men wearing shirts and ties along with strings of multi-colored beads, but this style eventually gave way to the collar necklaces, hatbands and beaded belts worn by contemporary Choctaw men. Both men and women wear sashes, known as the most traditional accessory, featuring both beadwork and appliqué.

Hilha (Dancing)

In the Choctaw culture, the tradition of dancing has a deep-rooted meaning. Instead of grand performances, dancing is meant for participation. Traditional dance cultivates pride in a Choctaw’s heritage. Dance groups represent most of the Choctaw communities, with styles reflecting those communities.

At the annual Choctaw Indian Fair, held every year for four days in mid-July, on the Choctaw Reservation, visitors have excellent opportunities to compare these community variations as they watch the dancers. Sometimes, the difference may be in a dance step; in other times, the chant – and rarely is the actual Choctaw language heard. When it is, the rise and fall of a chanter’s voice leads the dancers, and syllables carry a melody. The chanter usually keeps time by striking together a pair of sticks, called striking sticks.

There are three kinds of dance: war, social and animal.

War dances were used by early Choctaw to prepare for battle. They are unique in that the women join the men in dancing. In most other tribes, only men take part in the war dance.

Social dances mark important aspects of life such as friendship, courtship and marriage. They include stealing partners, friendship dance and wedding dance, among others.

Animal dances recognize creatures that were important to the Choctaw people and often mimic the behavior of their namesakes. Dancers dart in and out of the dance circle like playful raccoons in the raccoon dance or form a line that coils and uncoils in the snake dance.

The house dance is evidence of the Choctaw’s ability to adapt elements of other cultures to their own. Dancers use steps and movements from Anglo-American square dance and the French quadrille, while the fiddle accompaniment is adapted from Anglo-American tunes. The caller starts the dance and signals the dancers when it is time to move to the next step.

Music

As mentioned previously, dancing and music are not exclusive to each other in the Choctaw culture. In addition to dance, music is and has been a key element in other parts of Choctaw life.

One of the oldest traditional instruments that the Choctaw continue to use is the drum, which today is heard primarily at stickball games. The present-day Choctaw drum is modeled after military drums used by British and American troops in colonial times.

The body of the drum is wood or metal – more often than not the former. The wood used for this is usually sourwood, black gum or tupelo gum; the trees often are hollow by the time they reach a suitable size for drums.

Consider the beat of the drum as the heartbeat of the Choctaw people, and its sound announces an important event in the Tribal culture. It could precede dancers gathering, a game of stickball or a wedding ceremony. Drums can signal the start of each.

In most cases, the only musical instrument that the Mississippi Choctaw use to accompany songs is a pair of striking sticks. Slightly flat on two sides, the sticks have surfaces that are appropriate for hitting together. Dance chanters use them to keep time as they sing. In 1933, ethnomusicologist Frances Densmore visited Philadelphia, MS to record the songs of Choctaw chanters. She noted that striking sticks were used by most of the men who sang for her.

The violin, or fiddle, has also found its way into Choctaw musical traditions. Like many rural southerners, Choctaw turned to the fiddle for entertainment in their homes and communities. Fiddlers playing at house dances usually are accompanied by guitar players who provide a percussive rhythm. In the past, when no guitars were present, the rhythm was supplied by someone “beating straws.”

There is not a wealth of information to confirm that flutes, whistles and flageolets were used in Tribal events. But Mississippi Choctaw medicine men played vertical cane flutes on the night before and during stickball games in support of the home team. The flutes were nearly a foot long with a sound hole and two finger holes and were etched with symbolic designs.

Hopóni (Cooking)

As in many other cultures, food is a central part of the Choctaw Tribe. It is difficult to think of an aspect of Tribal life that food does not touch. All significant milestones and ceremonies involve – in one way or another – food and cooking. Celebrations like birthdays and weddings – even wakes – often consist of a meal.

Owing to Tribal history and heritage, a traditional Choctaw meal includes freshly grown vegetables, chicken, pork, frybread, desserts and sweet tea. For many years, the food on the table came straight from the garden and farm. Tribal families grew and harvested fruits and vegetables, raised livestock and hunted and fished to provide meals. While not unusual in rural areas, a pair of traditional Choctaw dishes remain staples of the Tribal diet: hominy and banaha.

At its core, hominy is a collection of dried corn kernels. After they are removed from the corn husk and cob, the kernels are left to cool and dry in order to kill seed germ inside. Preparers then use a kiti – a hollowed-out wooden log – to smash and pound the kernels into cornmeal used to make foods such as cornbread or grits.

It may sound relatively easy, but the cooking process can take several hours. The hominy must simmer over an open fire in a large cast iron pot filled with water. Once the water starts boiling, the cook adds the dried hominy with a type of meat in order to add flavor – sometimes chicken, other times pork or a combination of the two.

As the hominy is cooking, it must frequently be stirred in order to prevent it from sticking to the pot or burning. The preparer cannot forget about the fire, either. If available, this duty is typically handled by a male who is known as the firekeeper. This firekeeper’s role is extremely important because the fire has to remain at an even temperature throughout the cooking process. From start to finish, cooking hominy harkens back to time-honored traditions of growing and harvesting by Choctaw forebearers. But even in these modern times of electricity, cooking hominy outdoors is the best way to ensure its cooked properly and to the best consistency.

Another traditional dish commonly found at Choctaw tables is banaha – made by mixing field peas with cornmeal. One of the advantages of banaha is that the ingredients are available at a grocery store…or in a garden at home. It is another way for the Choctaw to follow the ways of the ancestors – an important part of Tribal culture.

To produce banaha, cooked field peas are added to cornmeal and stirred into a mush. They are then molded into small rectangles. Next, cornhusks are softened by soaking them in boiling water. Once the husks soften, the field peas/cornmeal rectangles are wrapped inside and tied shut with a strip of cornhusk. The banaha is then dropped into boiling water for 45 minutes to cook before serving.

Kabotcha Tóli (Stickball)

Imagine an empty field, two groups of warriors on either side with a steady drumbeat filling the air. It is time for a battle. Nope, this is not wartime…but it is close. A Choctaw game of stickball is both physical and intense; no wonder stickball has been called “Little Brother of War.”

Stickball has been a part of Choctaw life for hundreds of years and is among the oldest American field sports. Players use two handcrafted sticks, called kabotcha, carved from hickory and bent at one end to shape the cup of the stick. Leather or deer hide strings are tied to make the cup, in which the players catch and carry the ball. A woven leather ball, called towa, is made from cloth tightly wrapped around a small stone or piece of wood. Once it is wrapped to the desired size, the maker weaves leather strings over the cloth.

The basic concept of stickball is for each team to advance the ball down the field to the opposing team’s goalpost using only their sticks, never touching or throwing the ball with their hands. Points are scored when a player hits the goalpost with the ball.

The earliest historical reference to Choctaw stickball was a Jesuit priest’s account of a game around 1729. During the period, the Choctaw lived in towns and villages scattered across the area that is now southern Mississippi. When disputes arose between communities, stickball provided a peaceful way to settle the issue. These games were hard-fought contests that could involve as few as 20 or as many as 300 players. For most of the 20th century, players wore handmade uniforms consisting of pants hemmed just below the knee and open-necked, pullover shirts. They were made in the community’s colors and decorated with the diamond patterns found on traditional clothing.

Modern stickball has a few more rules than its historical predecessor, but the basics of the game still exist. A stickball game is played in four quarters. Time is dependent on the division: men play 15-minute quarters, women and 35-and-over groups play 10-minute quarters, and youth divisions play eight-minute quarters. Teams are allowed only 30 players on the field, which is now a football field with the goalposts in each end zone. Minor infractions can lead a player to sit out for a quarter, while major infractions can be either for the rest of the game or tournament. In the late 1970s, uniforms turned into gym shorts and jerseys in team colors. To this day, no padding of any kind is allowed on the playing field.

The World Series Stickball championship takes place every year during the annual Choctaw Indian Fair, held the second week in July.

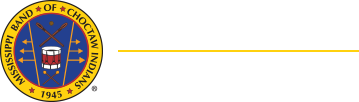

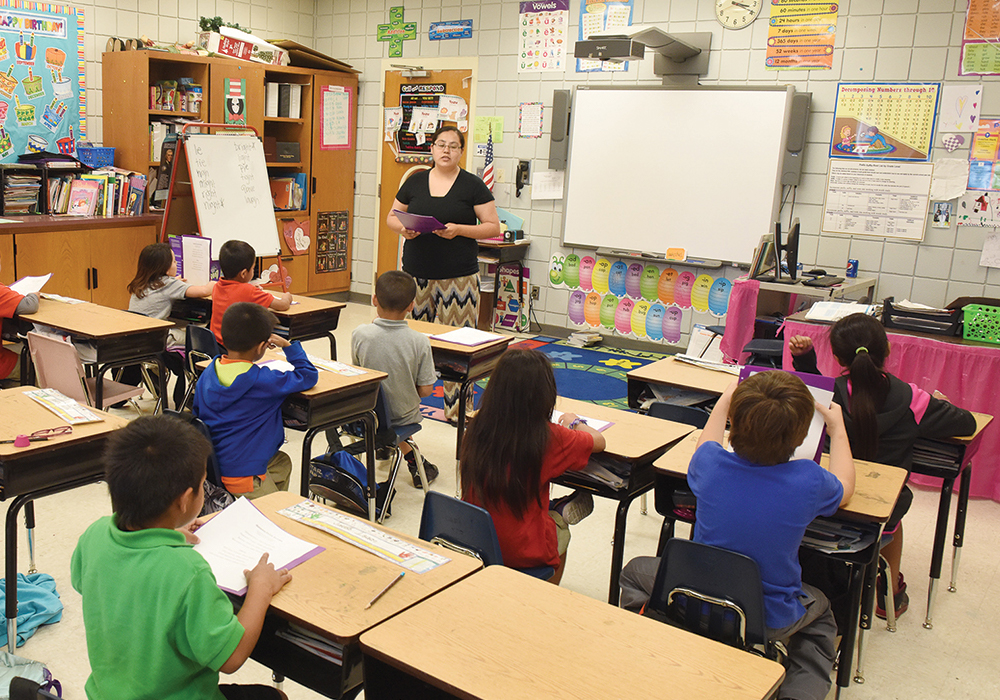

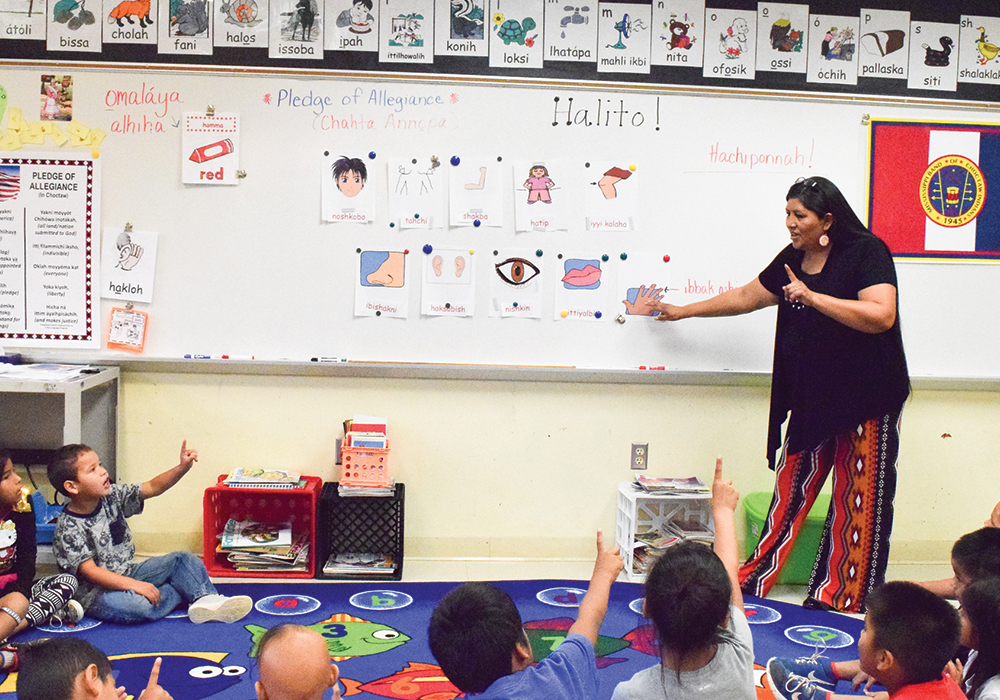

Chahta Annopa (Language)

From the past to the present, language is an important element of the Choctaw culture. Since its beginning, the Choctaw’s spoken language has passed on oral histories, legacies and cultural knowledge from one generation to another. The written Tribal language finds its roots in the 19th century during the period of the federal government’s forced “civilization policy”.

With tradition and identity being important aspects of Choctaw life, it is easy to see why language plays such a key role. The Choctaw language offers a link from the modern Tribe back to its forebearers through a common vocabulary. In fact, many of today’s Choctaw adults and elders are native speakers of their original Choctaw language; many of them only learned to speak English later due to English-language prominence in the non-Indian communities near the Reservation and the Choctaw’s need to interact with those English-speaking neighbors.

As part of daily life on the Reservation, the Choctaw language can be heard in administrative offices and is taught in the Tribal schools by certified language instructors. It is in the Choctaw communities and homes, though, where the language is most deeply rooted. While they encourage their children to hone their communications skills in English, most Choctaw parents also make sure that their sons and daughters speak Choctaw as well.

The modern Choctaw alphabet is a variant of the original created by Cyrus Byington – whose alphabet shares the same name. The Choctaw did not have a written language until Byington, a Christian missionary from Massachusetts, started to develop a system in the early 19th century. Following 50 years of comprehensive research, his efforts led to the Choctaw Definer (1852), Grammar of the Choctaw Language (1870), and a Choctaw Dictionary (1912). His work is considered one of the most thorough and complete lexicons for an American Indian language.

Choctaw words can be found throughout the state of Mississippi. Many towns, creeks and rivers are mispronunciations of Choctaw words that have led to current spellings far from its original Choctaw roots. Others are clearly Choctaw words that were changed to its phonic spelling, such as Bogue Chitto, taken from bók, meaning “creek,” and chito, meaning “big.” Our very own Neshoba County is actually the Choctaw word nashoba, meaning “wolf.” The next two are most likely misheard Choctaw words…Copiah Creek (also a county) is from kowi, meaning “panther,” and payah, meaning “to call,” and Tombigbee River is from itobi, meaning “box” or “coffin,” and ikbi “maker.”

Nanih Waiya

Nanih Waiya – a massive earthen mound and cave that has a significant role in the Choctaw culture is in Winston County, Mississippi. History suggests the mound and cave formation dates back more than 2,000 years and stands 125 feet above the surrounding land considered the “land of plenty” in the Choctaw migration story. Its name, Nanih Waiya, means “slanted hill” in the Chahta language. The cave mound, concealed by wetlands and pine/hardwood forests, is bordered by the slow moving Nanih Waiya Creek.

According to Tribal tradition, the Nanih Waiya site marks the birthplace of the Choctaw Tribe. That is where differing beliefs begin, however. One version holds that the Tribe emerged from the cave. The second says that the Nanih Waiya area was where the Tribe settled after a long journey from the west. Regardless, all Choctaw recognize Nanih Waiya as the heart of the Tribe and refer to it as the Mother Mound.

Although Choctaw history is irrevocably intertwined with Nanih Waiya, ownership of the cave and mound only recently returned to the Tribe. In 1830, the Choctaw ceded 11 million acres of land – including Nanih Waiya – to the United States as part of the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. In the years that followed, the state of Mississippi maintained Nanih Waiya as a state park, and the U.S. government formally recognized its significance when it placed the mound on the National Register of Historic Places. On August 8, 2008, the state of Mississippi returned the Nanih Waiya Mound to the Choctaw people. As a result, the Tribe celebrates Nanih Waiya Day on the second Friday of every August. At the same time, the Choctaw pledged to keep the Mother Mound under Tribal control forever.

The mound is open to the public; however, the cave is closed and requires permission by either the Office of Public Information or Choctaw Wildlife and Parks to obtain access. Tours are also available upon request by contacting the Office of Public Information at 601.663.7532 or filling out a Tour Request Form.

©2024 Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians