Choctaw History

Tribal History

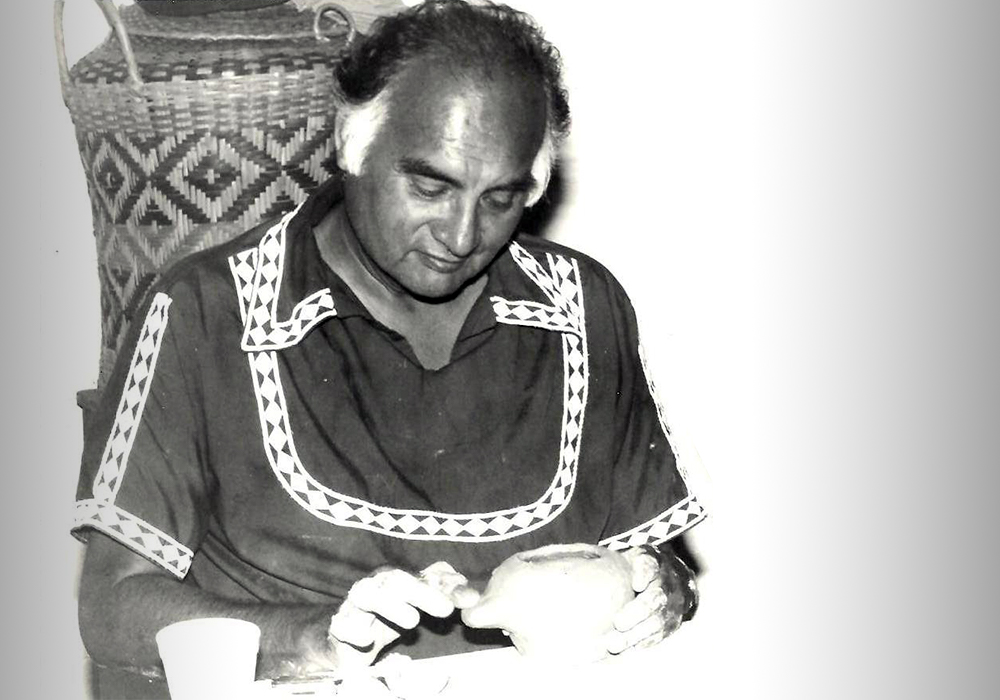

The Choctaw, and their ancestors, have called the region now known as the Southeast home for centuries. The proof of this is in the art, stories and legends of the Choctaw. There are three eras in which the Choctaw are known to have existed: Paleo-Indian Stage (18,000 – 8,000 B.C.), Archaic Stage (8,000-1,000 B.C.) and Prehistory (1,000 B.C. — 1540 A.D.). Prehistory is defined as the time prior to sustained European contact.

The first mention of the Choctaw name in modern history was recorded in 1675 by a Spanish priest in Florida. He warned early settlers against traveling too far to the west lest they meet the fearsome “Chahta”. This name is still what the Choctaw call themselves today.

The Choctaw’s first sustained contact with Europeans was French explorer D’Iberville in 1699. The two sides became allies for the following 65 years with the Tribe supporting the fledgling colony with both food and in wars against the English and Indians who supported the English. The alliance also provided the Choctaw with French firearms to fight other tribes that had been raiding the Choctaw for slaves since the early 1680s.

The end of the French and Indian War in 1763 put the Choctaw in a precarious situation. All lands east of the Mississippi River were transferred from the French to the English while French land to the west of the river went to the Spanish. That arrangement did not last long with the outcome of the Revolutionary War establishing the United States.

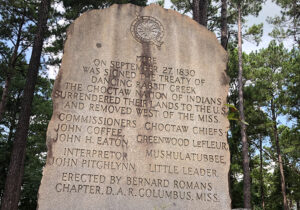

The United States and the Choctaw signed a number of treaties through the years that laid the course for the Choctaw’s future. The first, in 1786, reaffirmed the boundaries of Tribal land and reaffirmed Choctaw sovereignty. However, from 1801 to 1830, the Choctaw signed a series of treaties with the United States, which eventually led to the loss of all territory east of the Mississippi, some 32 million acres of land, and a move to present-day Oklahoma. Fortunately for the Choctaw, the 1830 Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek allowed Choctaw who did not want to go to the new territory to stay. Those who remained became U.S. citizens and were awarded land grants based on the size of each family. Some 4,000 Choctaw chose not to leave, despite a great deal of coercion.

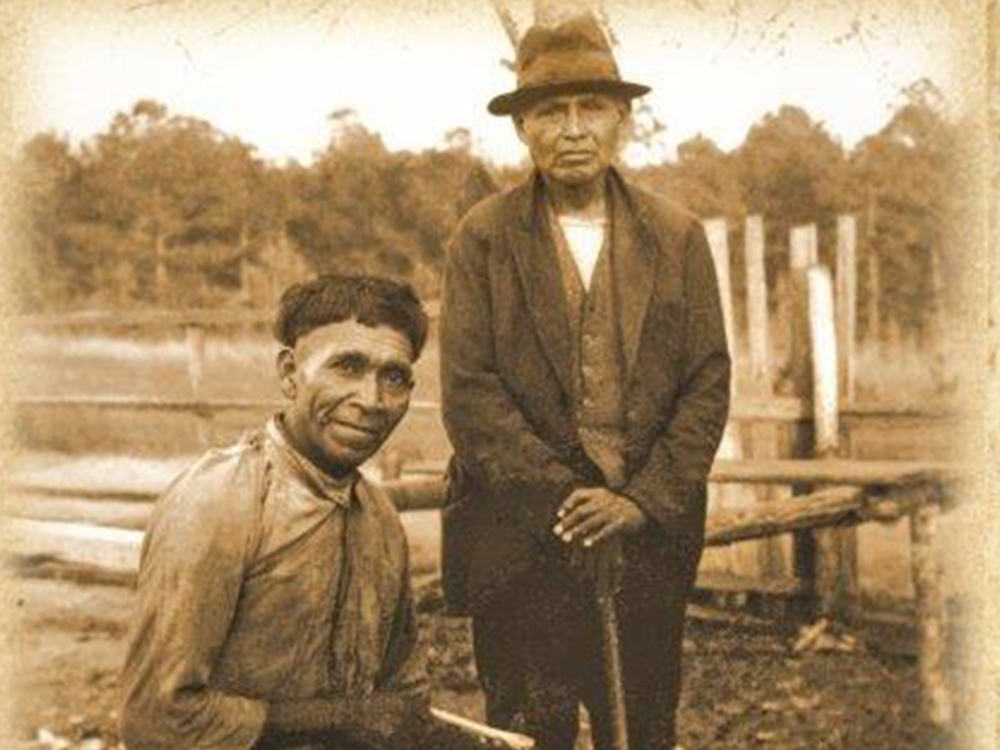

By 1850, virtually none of the Choctaw who had received land in Mississippi still retained it. They were either scammed out of their land or forced away by white settlers. As a result, many left for Oklahoma. Those who remained in Mississippi survived the rest of the 19th century by living off the land or becoming tenant farmers and sharecroppers on land that had once been theirs.

In the early 20th century, the poor conditions the Choctaw were living in were brought to the attention of the federal government. It stepped in to assist the Tribe when the 1918 influenza epidemic/pandemic killed more than 25 percent of the Mississippi Choctaw. During the 1920s, the Bureau of Indian Affairs established elementary schools in the main Choctaw communities as well as the Choctaw Agency and a hospital in Philadelphia, MS.

For many years the Choctaw living in the region worked tirelessly to gain recognition and establish themselves as a Tribe. Two separate groups worked towards gaining this recognition. It took them many meetings and years but using procedures authorized under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians’ Constitution was ratified in 1945 and officially recognized by the federal government. The first Tribal Council was little more than an advisory committee, set up to approve BIA decisions. As time went on, the council gained more authority and expertise, and eventually took over the direct administration of the Choctaw Reservation and its many programs.

Treaties

Treaties between the Choctaw and national governments date back to the early 1700s. The earliest ones dealt with trade and alliances with Great Britain, France and Spain. The nine major treaties with the United States (U.S.) are as follows:

Treaty of Hopewell (1786)

Signed on January 3, 1786 in Hopewell on Keowee river in South Carolina. The Tribe traded 69,120 acres in exchange for protection by the newly formed U.S. government. Those who signed the treaty were Benjamin Hawkins, Andrew Pickens and Joe Martin for the United States of America. Yockenahoma, great Medal Chief of Soonacoha; Yockehoopoie, leading Chief of Bugtoogoloo; Mingohoopoie, leading Chief of Hashoogua; Tobocoh, great Medal Chief of Congetoo; Pooshemastuby, Gorget Captain of Senayazo; and thirteen small Medal Chiefs of the first Class, twelve Medal and Gorget Captains.

Treaty of Fort Adams (1801)

Signed on December 17, 1801 at Fort Adams on the Mississippi. The treaty expanded the amount of Choctaw land ceded to the United States by 2,641,920 acres. In exchange the Choctaw Nation received a value of two thousand dollars in goods and merchandise and three sets of blacksmith’s tools. A regional famine earlier in the year decimated the Choctaw’s food supply. Those who signed the treaty were James Wilkinson, Benjamin Hawkins and Andrew Pickens for the United States of America and “Mingos principal men and warriors of the Chactaw nation of Indians.”

Treaty of Fort Confederation (1802)

Signed on October 17, 1802 at Fort Confederation on the Tombigbee River. The Tribe lost another 50,000 acres – with no compensation – after the U.S. claimed that the Choctaw boundaries from previous treaties were never clarified. Those who signed the treaty were James Wilkinson for the United States of America and “chiefs, head men, and warriors, of the said Choctaw nation.”

Treaty of Hoe Buckintoopa (1803)

Signed on August 31, 1803 at How-Buckin-too-pa. The Choctaw ceded more than 853,760 additional acres to the U.S. in exchange for forgiveness of Tribal debt to a U.S. trading company. The Choctaw chiefs at the signing, known as Commissioners of the Choctaw nation, received the following goods: 15 pieces of strouds, three rifles, 150 blankets, 250 pounds of powder, 250 pounds of lead, one bridle, one man’s saddle and one black silk handkerchief. Those who signed the treaty were James Wilkinson for the United States of America and two Choctaw commissioners Mingo Pooscoos and Alatala Hooma. Other Chiefs in attendance were those who resided on the Tombigbee.

Treaty of Mount Dexter (1805)

Signed on November 16, 1805 at Mount Dexter in Pooshapukanuk in Choctaw country. The Tribe ceded 4,142,720 acres to the U.S. In return, the U.S. established an annuity of $48,000 per year to the Tribe to pay debts to traders and merchants. Three great Medal Mingoes (Pukshunubbee, Hoomastubbee, and Pooshamattaha) were paid $500 for their services and would be paid an annuity of $150 during their time in office/service. Those who signed the treaty were James Robertson and Silas Dinsmoor for the United States of America and the three great medal mingoes, as well as, other Choctaw chiefs and warriors.

Treaty of Fort Stephens (1816)

Signed on October 24, 1816 at the Choctaw Trading House in Fort St. Stephens. The Choctaw traded 10,000 acres for a 20-year annual payment of $6,000 to aid in establishing tribal schools. The Tribe also received $10,000 worth of merchandise. Those who signed the treaty were John Coffee, John Thea and John McKee for the United States of America and “mingoes, leaders, captains, and warriors of the Chactaw nation.”

TREATY WITH THE CHOCTAWS, 1816.

A treaty of cession between the United States of America and the Chactaw nation of Indians.

JAMES MADISON , president of the United States of America, by general John Coffee, John Rhea, and John M’Kee, esquires, commissioners on the part of the United States, duly authorized for that purpose, on the one part, and the mingoes, leaders, captains, and warriors, of the Chactaw nation, in general council assembled, in behalf of themselves and the whole nation, on the other part, have entered into the following articles, which, when ratified by the president of the United States, with the advice and consent of the senate, shall be obligatory on both parties:

ARTICLE I. The Chactaw nation, for the consideration hereafter mentioned, cede to the United States all their title and claim to lands lying east of the following boundary, beginning at the mouth of Ookitibbuha, and the Chickasaw boundary, and running from thence down the Tombigby river, until it intersects the northern boundary of a cession made to the United States by the Chactaws, at Mount Dexter, on the 16th November, 1805.

ART. II. In consideration of the foregoing cession, the United States engage to pay to the Choctaw nation the sum of six thousand dollars annually, for twenty years; they also agree to pay them in merchandise, to be delivered immediately on signing the present treaty, the sum of ten thousand dollars.

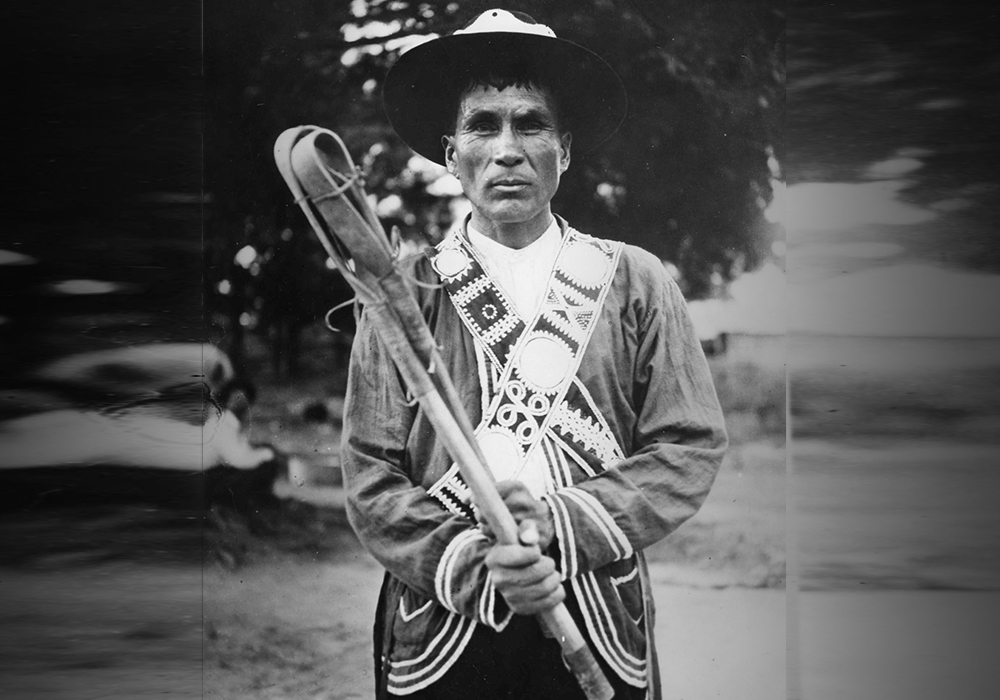

The seventh treaty, the Treaty of Doak’s Stand, involved a land swap. The head negotiator for the United States was Andrew Jackson. The treaty, signed on October 18, 1820, provided for the exchange of 5,169,788 acres, the southwestern one-third of the remaining Choctaw land fronting the Mississippi River, for a wild tract (13,000,000) of Quapaw land lying beyond the Mississippi River between the Canadian-Arkansas and Red rivers, comprosing the southern half of the present state of Oklahoma and a large area in Arkansas. Before the Treaty of Doak’s Stand, the United States had taken the land from the Quapaw for about $4,000 plus a $1,000 annuity. Intimidation, as well as bribery, was used to persuade the Choctaw to swap their extremely valuable delta land for the 13 million acres in the West. The Choctaw resisted, because the western land would not be of use to them unless they agreed to removal. For the first time, the idea of removal was openly discussed. Before the Choctaw could reach their new land, the part of it that lay in Arkansas was settled by white pioneers. It is particularly noteworthy that the Treaty of Doak’s Stand traded to the Choctaw all the land they were ever to receive in present-day Oklahoma.

Treaty of Doak’s Stand (1820)

Signed on October 18, 1820 at Doak Stand on Natchez Road. The Tribe traded 5,169,788 acres of land in Mississippi for 13,000,000 acres of land west of the Mississippi River, that later became the state of Arkansas. The Choctaw who stayed on the ceded land to the U.S. could receive land if they “become so civilized and enlightened as to be made citizens of the United States.” (Article 4) Those Choctaw families (Warriors) who voluntarily removed were provided “a blanket, kettle, rifle gun, bullet moulds and nippers, and ammunition sufficient for hunting and defense, for one year.” The Warrior (head of household) was supplied with corn for a year to support his family and during the time it took to travel to this new land ceded to the Choctaw by the U.S. (Article 5) The U.S. was to appoint an agent, for the benefit of the Choctaw, to live on this new land to the West. A blacksmith would also settle in the “point most convenient to the population.” (Article 6)

Schools to educate the Choctaw would be paid for by selling a portion of the Choctaw ceded land in fifty-four one-mile sections. (Article 7) The annuity set up for schools in the Treaty of 1816 was kept in-tact. (Article 8)

This treaty also noted those Choctaw Chiefs and Warriors who did not receive compensation for their service to the United States during the Pensacola Campaign shall be paid whatever is due to them. (Article 11) Each Choctaw district would be given $250 from the United States to organize a corps of Light-Horse, consisting of 10 in each District to maintain order. (Article 13) The treaty also allowed for Chief Mushulatubbee to continue to receive his father’s $150 annuity that was established in previous treaties. (Article 14)

Those who signed the treaty were Andrew Jackson and Thomas Hinds for the United States and the three Medal Mingoes Puckshenubbee, Pooshawattaha and Mushulatubbee, as well as chiefs and warriors of various Choctaw Districts.

Treaty of Washington City (1825)

A delegation of Choctaw traveled to the City of Washington to correct the Treaty of Doak’s Stand because the land in Arkansas, designated for the Choctaw, was previously settled by white people who were citizens of the United States. The Choctaw ceded 2,000,000 acres of land originally ceded to them in the Treaty of Doak’s Stand that was previously settled. Other inaccuracies were also “fixed”. In consideration of the cession, the United States agreed to pay the Choctaw Nation $6,000/annually forever, with the first 20 years being in support of schools and the “instruction in the mechanic and ordinary arts of life.” After the first 20 years it was agreed the said annuity “may be vested in stocks, or otherwise disposed of, or continued, at the option of the Choctaw nation.”

Article 11 of the Treaty of Doak’s Stand had payments to Chiefs and Warriors for their service. This was being delayed due to improper vouchers. The United States agreed to pay the Delegation $14,972.50 for them to take back and distribute to those chiefs and warriors who served in the Pensacola Campaign.

Chief Puckshenubbee, a member of the Choctaw delegation, passed away while traveling to the convention. His successor, Robert Cole, would start to receive the annuity paid to Chief Puckshenubbee.

The convention took place on January 20, 1825 in the City of Washington between John C. Calhoun for the United States and the Choctaw delegation which consisted of Mushulatubbee, Robert Cole, Daniel McCurtain, Talking Warrior, Red Fort, Nittuckachee, David Folsom and J. L. McDonald.

Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek (1830)

“A treaty of perpetual friendship, cession and limits” began September 15, 1830 and was held at Dancing Rabbit Creek. The U.S. sought to remove the Choctaw from Mississippi under authority of the Indian Removal Act and move them westward to Oklahoma. Under terms of the treaty, the Tribe ceded their remaining 10,423,139.69 acres in Mississippi. Article III of the Treaty states “the Choctaw nation of Indians consent and hereby cede to the United Sates, the entire country they own and possess, east of the Mississippi River; and they agree to move beyond the Mississippi River, early as practicable.” The plan suggested in the treaty was for a group “not exceeding one half” depart during the falls of 1831 and 1832. The remaining to following the seceding fall of 1833.

Only approximately 4,000 Choctaw remained in Mississippi, and under treaty terms were granted U.S. citizenship. The descendants of those who remained are now the members of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians.

* To see a complete listing of agreements and treaties of the Choctaw, please contact Choctaw Archives at the Chahta Immi Cultural Center.

* To see full treaties visit the National Archives catalog website at https://catalog.archives.gov/

Choctaw Today

Today, the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians (MBCI) is the state’s only federally-recognized Indian Tribe. Enrolled membership in the Tribe exceeds 11,000 individuals, all of whom have at least a 50 percent degree of Mississippi Choctaw blood. Two-thirds of the Tribal population is under the age of 25.

Tribal lands contain a diversified portfolio of manufacturing, service, retail, hospitality and construction enterprises. Each provides employment opportunities for Tribal members and area residents, as well as tax-equivalent revenue to provide Tribal government services.

The Mississippi Choctaws now own approximately 34,000 acres.

Our Services Include:

Health center and clinics

Family and community services

Public safety

Education

Land management and environmental resources protection

Road and infrastructure improvements

Youth and adult recreation

Employment opportunities

The revenues fund construction of new schools, strengthen educational programs and post-secondary scholarships for Tribal members. The success of Choctaw businesses and enterprises enables the Tribe to become more self-reliant and self-sufficient, while making a significant and favorable economic impact on the surrounding non-Choctaw communities. The Tribe is now among Mississippi’s top five largest private employers, with more than 5,750 employees.

©2024 Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians